Fun facts about Mt. Shasta

As any Adventure Treks student who has climbed Mt. Shasta can tell you, this mountain has a lot going on. From spectacular beauty and long-range views to spectacularly strange claims of extraterrestrial activity, the history and folklore of one of our favorite mountaineering destinations is worth looking into. Here are 10 things you may not know about Mt. Shasta.

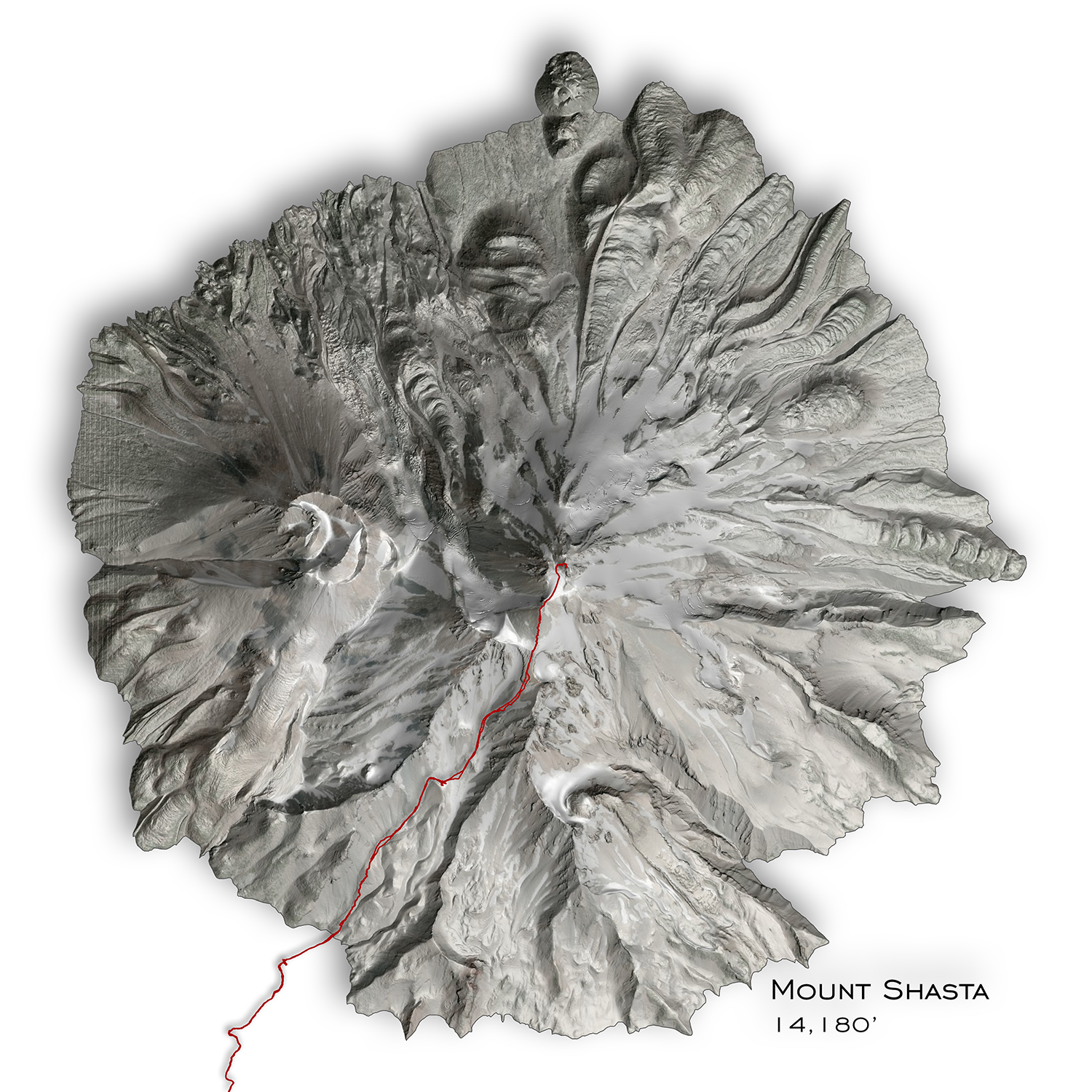

1. Mt. Shasta is TALL. At 14,179 feet, it is the second-tallest mountain in the Cascade Range and the fifth-tallest in California. The mountain looks so striking and prominent because its summit is nearly 10,000 feet above the low hills and valleys that surround it. (See number 5 about the route Adventure Treks students take to the top.)

2. California’s largest national forest houses this landmark. Two separate forests were established in 1905—the Trinity National Forest and the Shasta National Forest—and were combined in 1954. Now, the Shasta-Trinity National Forest covers 2.2 million acres of northern California, and Mt. Shasta is its highest point!

3. Avalanche Gulch, the route Adventure Treks generally takes to climb Mt. Shasta, is considered the least technical way to the summit. With more than 7,000 feet of elevation gain in six miles, it may not require advanced rock climbing or glacial travel skills, but it certainly packs a challenge.

At right, a topographical map of Mt. Shasta including our students’ route (Avalanche Gulch), made by AT instructor Ian Petersen. Check out Ian’s beautiful, artistic topo maps at mapyouradventure.com, and see his maps specific to Adventure Treks trips here!

(The intense effort, teamwork, and grit—and thus incredible reward, unforgettable memories, and strong sense of achievement—involved on this climb means it’s often a topic discussed in college essays!)

4. There are seven named glaciers on the mountain. The Whitney, Bolam, Hotlum, Wintun, Watkins, Konwakiton, and Mud Creek glaciers keep Mt. Shasta’s slopes white year-round. Unfortunately, during summer 2021’s record heat waves, some of these glaciers split into smaller pieces, and all of them experienced rapid melting. The first snow of the season fell at high elevation this October, so here’s hoping for a heavy snowpack this winter, which makes for a safer and easier climb in summer!

5. The view of Mt. Shasta’s summit is often obscured by lenticular clouds. When air passes calmly over high points in a landscape, moisture can condense into lens-shaped clouds. These clouds are often said to look like UFOs, which brings us to:

6. Mt. Shasta might be full of aliens. There are many theories involving extraterrestrials on, in, and around the mountain, often proposing that the unique lenticular clouds are strategically placed to hide a spacecraft landing near the summit. Another theory proposes that the Lemurians, humanoid inhabitants of a hypothetical ancient land bridge that sank beneath North America, became trapped inside the mountain and built their society within.

7. But back to the facts. Mt. Shasta is a stratovolcano and, along with the rest of the Cascade volcanoes, forms part of the Ring of Fire.

8. The Shasta-Trinity National Forest is the ancestral homeland of many native peoples. The Winnemem Wintu tribe consider a natural spring on Mt. Shasta’s slopes to be the place where their people came to be. Other tribes believe the mountain holds the creator of the universe. Thirteen different tribes work with the National Forest Service to protect their access to sacred sites on and around the mountain.

9. Mt. Shasta is known as the root chakra of the world. Chakras are an ancient concept of energy sources throughout the body—on the globe, the chosen sites are places with a particularly strong energy that pull visitors for a variety of reasons. Other sites include Uluru, Stonehenge, the Great Pyramids, and Mt. Kailas.

10. About 300,000 years ago, Mt. Shasta mostly collapsed, forming one of the largest landslides in history. Many of the hills surrounding the base of the mountain (they’re called hummocks) are not hills at all, but rather piles of old volcanic rock.

Sources:

Synthetic: Synthetic insulation comprises long, very fine strands of plastic, piled together to form a fluffy, gauzy-like material, typically formed into sheets and sewn in place between the outer fabric and lining of the product. Because the insulation is plastic, it’s naturally water-resistant and will not collapse and “mat” together when wet. Synthetic items allow the warm air to continue to be trapped against the skin and maintain an insulative property even while wet. Synthetic insulation is almost always less expensive than down insulation, but it will be slightly heavier and bulkier than its down counterpart.

Synthetic: Synthetic insulation comprises long, very fine strands of plastic, piled together to form a fluffy, gauzy-like material, typically formed into sheets and sewn in place between the outer fabric and lining of the product. Because the insulation is plastic, it’s naturally water-resistant and will not collapse and “mat” together when wet. Synthetic items allow the warm air to continue to be trapped against the skin and maintain an insulative property even while wet. Synthetic insulation is almost always less expensive than down insulation, but it will be slightly heavier and bulkier than its down counterpart.